Irish Autism Action pointed me to a piece picked up by Yahoo news from October 25th, written by staff from the Coalition for Mercury-Free Drugs (CoMeD) . It is a critique of sorts, of a paper published in Pediatrics, in 2003, on “Thimerosal and the Occurrence of Autism: Negative Ecological Evidence from Danish Population-Based Data” which may be read (free, thanks to the AAP) here.

The paper first.

It is written by seven Danish scientists. Poul Thorsen, of whom more later, is the fourth author. To understand the importance of this paper, you need to know that Denmark has one of the best health information systems in the world. The vast majority of contacts between Danish residents and their health services are recorded, with a unique identifier, which allows one to identify the first contact, and to avoid counting the same people twice. This system is reliable, not infallible, but far better than equivalent systems in the UK. There are no such systems in Ireland.

Thiomersal or Thimerosal

Thimerosal or Thiomersal is a chemical, containing mercury. In the body it is converted to ethylmercury. A lot is known about the toxicity of a related compound, methylmercury, which caused the terrible tragedy of Minanmata disease. Much less is known about the toxicity of ethylmercury, but it is felt to be wise to assume that it too is toxic. Thiomersal has been used as a preservative in multi-dose vaccine vials for many years, but, because of concerns about possible toxicity, is now largely phased out in the EU, and the USA. There has been an extensive controversy about the links between thiomersal exposure in infancy and childhood, and the development of childhood autism.

What the Danish paper adds

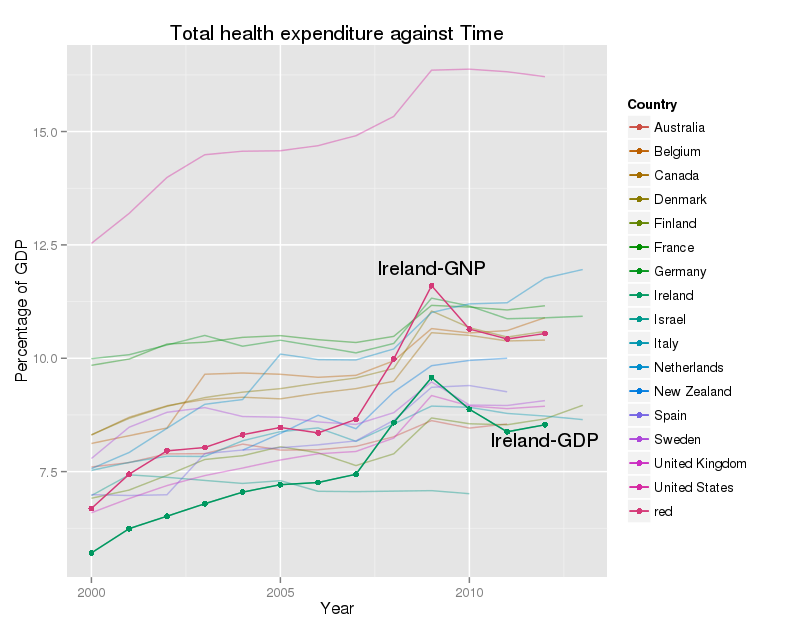

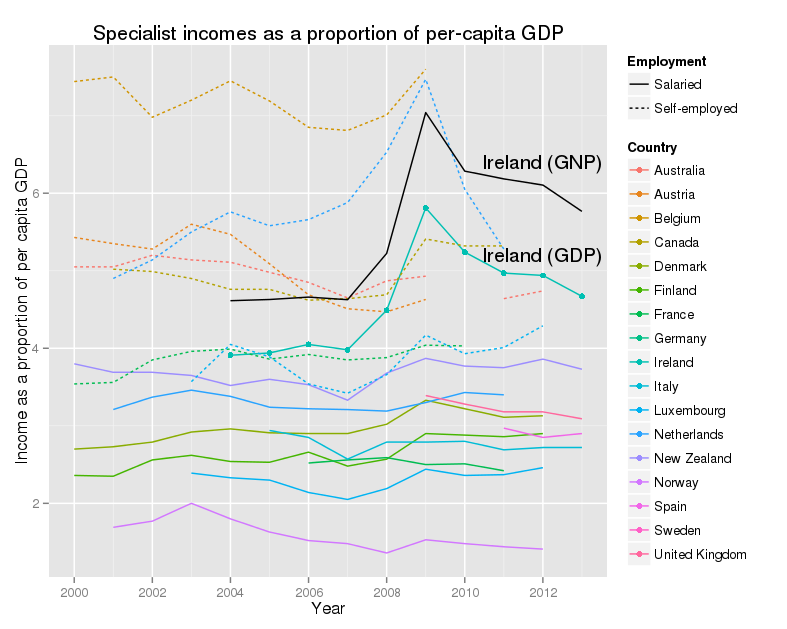

The Danes analyzed first diagnoses of autism, (the ‘incidence’ of autism in the jargon of my profession), in children, aged between 2 and 10, and diagnosed between 1971 and 2000. Thiomersal was used as a vaccine preservative up to March 1992. They found just under 1000 cases of autism diagnosed in Denmark over this period. The rate of occurrence of autism is shown in Figure 1 from their paper.

Briefly this shows autism rates low, and steady from 1971 to about 1987 or 1988. After this autism rates rise steadily, first in the youngest children (ages 2 to 4), then in the next group (ages 5 to 6), and finally in the oldest children, (ages 7 to 9). These are children newly diagnosed with autism. Rates are beginning to dip in the two older groups in 2000, as compared with 1999. The vertical line on the graph, in 1992, shows when thimerosal containing vaccines stopped being produced in Denmark.

What does this mean?

This graph shows a significant increase in the incidence of autism. This is similar to that recorded in many other countries at the same time. No-one really knows the cause of this increase. It is widely believed by experts that a big part of it is due to a mix of better access to child psychiatric services, better and more rigorous diagnosis, and to the broadening of autism diagnoses into the Autism Spectrum disorders (see the recent review by Fombonne). This does not mean that some part of the increase may not be real, but it is widely believed that most of it reflects other things besides a real increase in autism.

There are also specific factors which very likely contributed to the rise in Denmark – and are mentioned in their paper. First they moved classification systems, for autism, and all other diagnoses, in 1994, from ICD-8 to ICD-9. Secondly, outpatient diagnoses were accepted from 1995, but the authors examined inpatient diagnoses separately, and found the same pattern in these data. They did not show the inpatient only data, but this is a common practice, enforced by editors, when there is pressure on space in published papers.

It’s easier to say what this does not mean. If you believe that thiomersal in vaccines caused any significant proportion of cases of autism, you should no longer believe this. I can think of no mechanism by which removing a major cause of autism, could lead to a rise in the incidence of the syndrome. The dip in incidence in 2000 is interesting, though modest, but cannot be related to the removal of mercury from vaccines eight years earlier.

And the scandal?

The COMED story makes two specific allegations

- The authors suppressed data from 2001, which showed a further fall in autism prevalence. CDC officials knew about this.

- One of the authors, Poul Thorsen, has been sacked by his employers, Aarhus university, and is under investigation for large scale financial fraud against the US government, related to grants for autism research.

So, let’s take these in order.

Suppressing data?

First, the fall in autism incidence in 2001. As I mentioned the paper shows data up to 2000, with some indication that incidence is falling in 2000 compared with 1999. The email mentioning the 2001 data is largely redacted, so it’s hard to make much sense out of it. But if we suppose that the rate had indeed fallen further, what implication does this have for the published paper? The paper shows clearly a large increase in autism incidence starting a few years before thimerosal was removed in 1992, and continuing at the same pace for at least six further years (up to 1999). Removing thimerosal in 1992 cannot affect autism rates in children aged 5 to 6 in 2000, it is simply impossible. Neither can it affect rates in 2001.

Many scientists in my discipline struggle with the ‘just one more year’ problem. Data are seldom complete on December 31st. It takes time to clean data, to check it, and to make it available. It then takes more time to get it, analyze it, and write a paper about it. By then the next year’s data may have come out. Most of us decide, usually after a quick look at the new data, if we want to hold up the paper for another six months while we repeat the process. At some point, you just have to publish. This is life, not a scandal!

Poul Thorsen

First, a declaration. I know Dr. Thorsen. I have met him two or three times, when I was working on a study to design methods to estimate the prevalence of autism across Europe. If, as alleged, he has defrauded scientific funds paid by the US, to Aarhus university for autism research, I do not defend him. However, even if every charge in the grand jury indictment were proved, I do not see that this ought to affect how we read the paper.

Thorsen was one of seven authors, and was neither the first, nor the last, the two most significant slots in our business. The paper was not funded by his research funds, and had no organic connection with them. No allegation of scientific fraud has been made against him. An ancient, and disreputable debating strategy is the ‘ad hominem’ attack – I can’t attack what you say, so instead I will attack you. Scientists didn’t attack Andrew Wakefield personally, they attacked his paper, because the conclusions he presented, did not follow from the evidence he presented. Similarly, an attack on Poul Thorsen, justified, or otherwise, does not speak to the correctness, or otherwise, of this paper.

One swallow does not a summer make

One of the mottoes of my profession is ‘Never believe one study’. Any single study can come up with a completely wrong answer, no matter how well it is done, no matter how skilled, conscientious, and honest, those who work on it. In the case of thiomersal and autism, there is a small flock of good studies, all saying pretty much the same thing – there is no evidence for a causal link between autism and thiomersal exposure. The paper by Madsen et al. is only one of the flock, but it is flying in the same direction as the others.

Is thiomersal safe?

Many countries still need to use thiomersal, because it is cheap, effective, and allows vaccines to be used safely in hot climates. We don’t use it, because we can afford not to. José G. Dórea, from the Universidade de Brasilia in Brazil, has a very thoughtful review article assessing the evidence, and concludes that, if we have to use it, and Brazil does, we need to be very careful with thiomersal in babies. He finds no good evidence of harm, but this not the same as evidence of safety. If thiomersal has to be used, there are steps that can be taken to protect and develop babies’ brains in other ways, and these ought to be adopted widely in any event. I would fully agree with him.

Scandal?

I do not speak for the Coalition for Mercury-Free Drugs, and I make no assertion about their objectives in writing this story. However, they are wrong. There is no scandal here, and the problems they identify with the paper are acknowledged and addressed by the authors. There is a

long report, sent by CoMED, to Béatrice Sloth of the Secretariat for the Danish Committees on Scientific Dishonesty, which forms, I think, the basis for the press release. I have read it carefully, and I see no evidence of scientific wrong-doing in the report. There are critcisms of the paper, but the major scientific issues raised, the change in diagnosis codes, and the inclusion of outpatient care, are addressed in the paper by the authors. This is not stated in the report.

All in all, this is a non-story. It is typical of too many others, written by people who seem to only half understand the science, and seemingly intended to strike fear into the hearts of parents. Some children died, and many more were unnecessarily brain damaged, by the original measles vaccine scare. Is that not enough? Isn’t it time to stop?