Our nearest and dearest neighbours are engaged in leaving the European Union. For Ireland, the experience may be less like the neighbours moving, than them moving, taking their house, garden, the road outside, and possibly the party wall, as they head off to roam the world. As a result, like most other EU countries, Ireland is spending a lot of time on damage limitation. There’s been a good deal of attention paid to key sectors of our economy, agriculture, and finance, and our politics, notably the rights of Irish citizens in the UK post-Brexit, and the Northern Ireland peace process. I suggest that we need to look at some other sectors of our society, and I’m going to explore some of the possible impacts on health and social care. Together with the DCU Brexit Institute, I’m running a meeting in the City West Hotel in Dublin on May 3rd next. Tickets are free from EventBrite, but you are asked to book in advance.

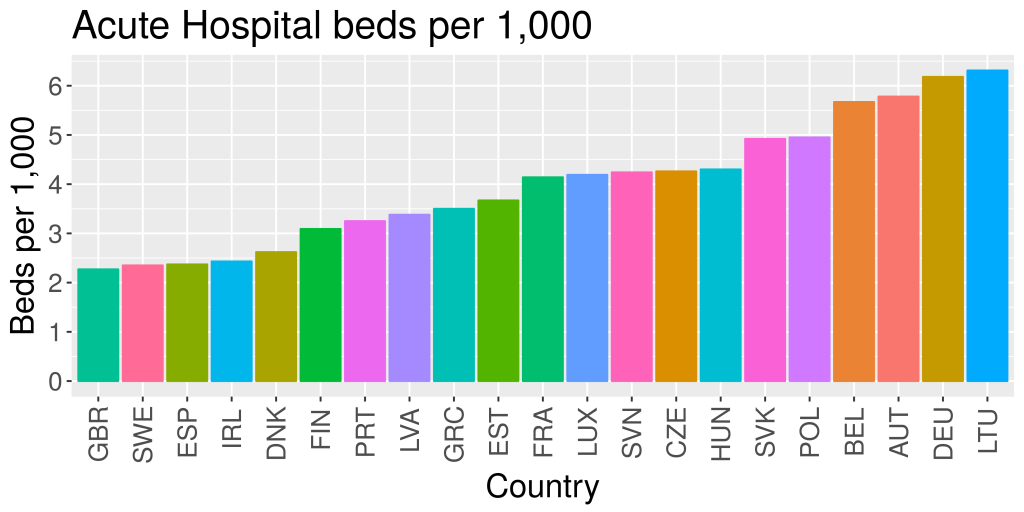

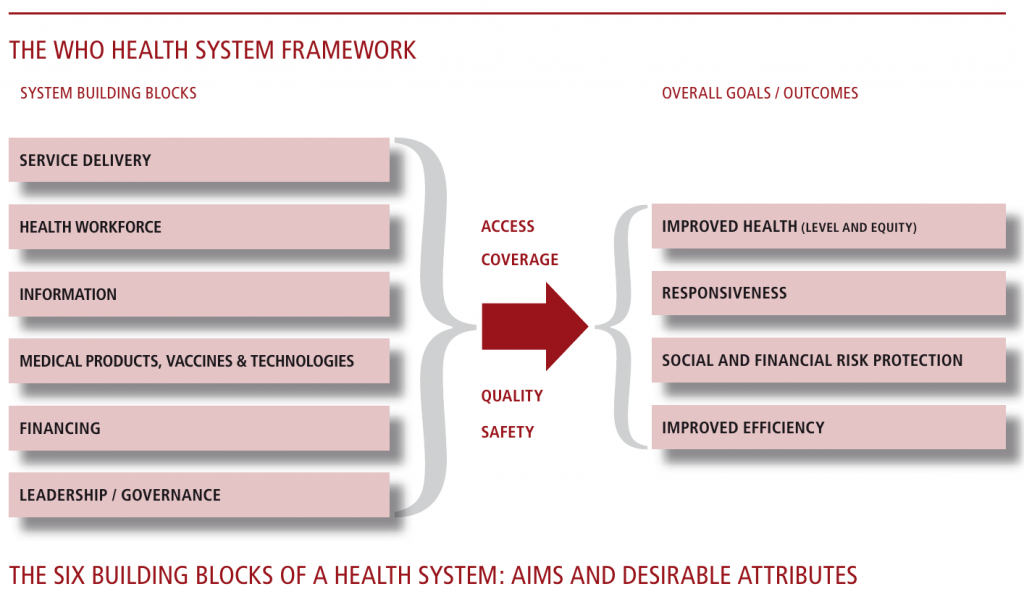

Nick Fahy and colleagues have written a paper in the Lancet which looks at three possible scenarios for Britain. They describe these as a ‘soft Brexit, hard Brexit, and failed Brexit’ respectively. These are respectively a deal similar to the EEA, a deal similar to CETA, and no deal, with WTO terms of trade. None of these is particularly cheerful. They have chosen to use the WHO Health System Framework (See figure) for their analysis, and so am I.

WHO Framework for Health systems (Source :- World Health Organization. Everybody’s business – Strengthening health systems to improve outcomes. WHO’s Framework for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007, Page 3.)

For the UK, Fahy and his colleagues find little to cheer about. Working through each of the six building blocks, only two positives emerge – it might be possible to improve regulation of professionals, and it might be possible to improve working conditions for staff. I think it would be fair to say that the authors are by no means sure that any of these benefits will happen.

For Ireland, things are more complex. We are not leaving the EU, but we will be more distant from the UK than at present. Working through the building blocks, and following Table 2 in their paper we get :-

| Item | Impact |

| Workforce | Significant and adverse |

| Recruitment and retention of staff | Likely to be harder, as Irish staff will be allowed to work freely in the UK, so demand will increase for Irish trained staff to replace other EU and non-EU staff members. |

| Mutual recognition of professional qualifications | Unknown, but would be easy for the UK regulators to continue to recognize Irish qualifications. It may be much harder for the EU to recognize UK qualifications. |

| Employment rights for health workers | May be much harder to employ UK trained staff until final rules are settled. |

| Financing | Uncertain impacts, but could be locally very severe. |

| Reciprocal health-care arrangements | It’s very unclear what the impact will be. At the moment Irish people, resident in the UK, can use the NHS on the same basis as UK citizens. UK citizens in Ireland are covered by reciprocal arrangements which predate the EU by many years. How these will be affected by Brexit is not known. |

| Capital financing for HSE | Depends on the impact of Brexit on the Irish economy |

| Indirect impact on health service financing | Depends on the impact of Brexit on the Irish economy |

| Medical products, vaccines, and technology | Substantial adverse effects, damaging the wider economy as well as the health economy. |

| Pharmaceuticals | There will be a serious impact on one of our major exports. Some items are sourced only from the UK, and supply may be disrupted for a period of time. Many more items, form the EU, and further abroad, are distributed from UK distributors, and these channels may be disrupted. |

| Other medical products | The effect on human products, such as blood and organ donations is unknown at present. There may be serious disruption of our medical device exports, and there could be major problems with contracts for maintenance of machinery, which is currently done by UK suppliers. |

| Information | There may be grave difficulties sharing electronic medical information with clinicians in the UK. The redeeming feature is that this is seldom done now, so the practical impact may be very small. |

| Service delivery | Potential for significant degradation of services |

| Working time legislation | No effect |

| European Reference Networks | There will be a big loss to us – many of our links for rare diseases are with UK specialists and hospitals, and these will need to be protected. The UK is very active in European rare disease care, and it will be very challenging to replace their inputs. |

| Cross-border care | There will be a big loss both to Northern Ireland and to us. There is a network of joint services which will be very challenging and very costly to unpick. The impact may be very serious, especially in border areas, where sophisticated joint arrangements have been established. Some services are directly threatened, for example the joint HSE/NHS cancer service in Derry. |

| Leadership and governance | |

| Public health | The impact may be significant, especially if there is a hard Brexit. |

| Competition and trade | The impacts are very substantial and mostly negative. It will cost more, be slower, and harder to trade with the UK, and the rest of Europe after Brexit. |

| Research | Very significant. Many of our closest and most effective research links are with UK partners. |

| Scrutiny and stakeholder engagement | Not applicable |

Summary

The economic impacts of Brexit have been well studied. Ireland’s physical exports are dominated by medicines and medical products, and the effect of Brexit on these will be significant. However, there are other health sector impacts of Brexit, and some of these have been discussed here. There are doubtless more.

These problems by not insuperable. The challenge is that health is nowhere near the top of anybody’s Brexit agenda. There is a risk that nothing will be done in time to mitigate these risks. Earlier this month, the ECB and the Bank of England set up a joint task force to keep the financial markets running, should there be a hard Brexit. Perhaps we need something similar for the health sector?