The IMO organized a meeting on Wednesday evening in Buswell’s Hotel in central Dublin, just across from the Dáil (the Irish parliament building) on the topic of ‘Solving the Chronic Disease Problem – through General Practice’. It was packed out, and there was a very good line up of speakers, starting with Leo Varadkar, who trained as a GP and is now the Minister for Health, and including three prominent GP’s Austin Byrne, William Behan, and Tadhg Crowley. We also had spokespeople from a selection of the political parties, Sinn Fein, the Social Democrats, Fianna Fail and Fine Gael there.

The problem

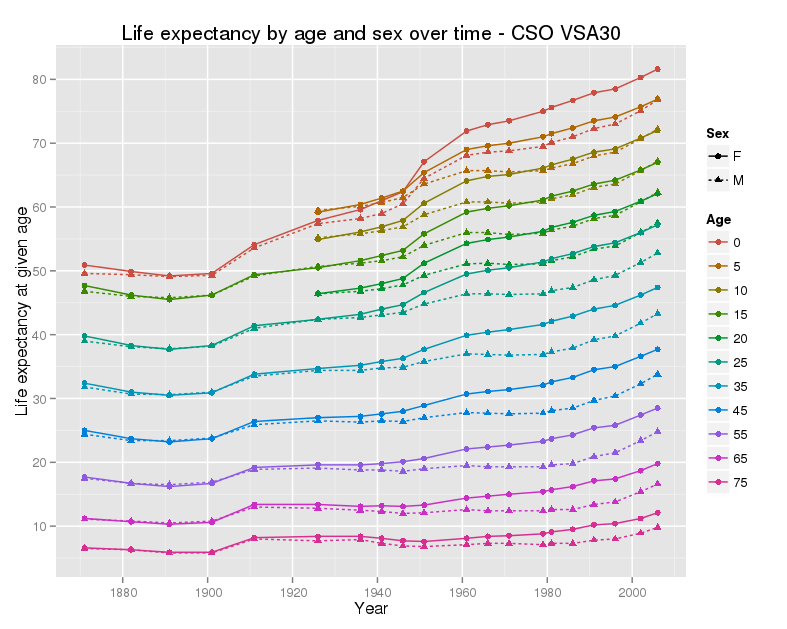

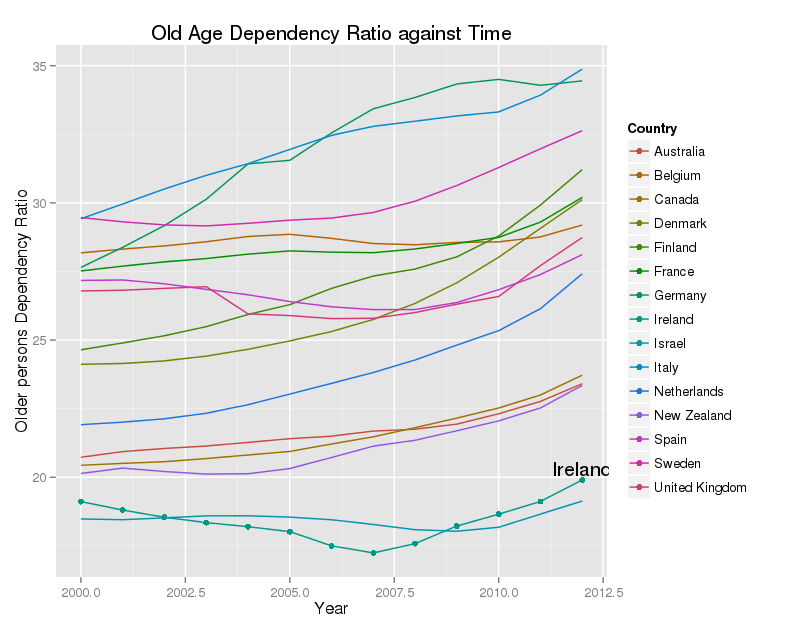

Ireland has a very young population by EU standards, with a low proportion of people aged over 65. However, that proportion has been growing rapidly since 2005, and is expected to continue to rise quite quickly, until 2040 or so. There are approximately 25,000 more people over the age of 65 every year, of whom approximately 5,000 will be over the age of 85.

This poses two challenges – first how do we pay for healthcare for the larger number of elderly people, and second how do we deliver it efficiently and fairly. (It’s worth pointing out that the panic about herds of older people roaming the streets in the future, demanding healthcare and pensions, is overstated. Most healthcare costs are incurred in the year or two before death anyway, and the usual measures of dependency ignore the quite large economic contributions of those over 65).

A rapid increase in the numbers of older people does pose a challenge – specifically the challenge of dealing with more cases of chronic disease, and more people with more than one chronic disease – people affected by ‘multimorbidity’. Unless this is met, and reasonably resourced, there will be severe problems.

The question

The question posed by the speakers last night was, fundamentally, can the Irish health service cope with these demands by business as usual, and the answer was an unequivocal no.

Too much care for people with chronic disease takes place in acute hospitals, or in private clinics, and that care is fragmented. Irish hospitals are at, or very very close to, capacity, with bed occupancy of 98% – far higher than they should be. They reviewed evidence showing that integrated care, led by GPs, can give a better quality of care, and can reduce the use of expensive health care, including hospital admissions, specialized investigations, and outpatient visits. For a small group of complex patients, a small group who account for upwards of half of total health expenditure, costs can be reduced by 10% to 20%.

The answer

They proposed a model of greater investment in general practice, with more care moving to the community, and much better access to hospital services, and special investigations, for GPs. This pattern of care would, very likely, improve patients’ experience of health care, improve the health of the population, and reduce costs.

Part of this would be a better GP contract. The current GMS contract forbids chronic disease management, and indeed 25 years ago, inspectors would go out to practices to make sure that GP’s were not managing high blood pressure in their GMS patients. However, a model where chronic disease care comes in piece by piece, over many years, will not work either. GP’s already know how to do chronic care, they just need to be resourced for it.

The politicians

The politicians sort of got it. Their biggest weakness was the failure to separate out general practice and primary care services. In Ireland primary care means HSE provided primary care, delivered by state employees. GP’s are private contractors. Their biggest threat was their universal view that the health care budget could not and would not rise much over the next few years.

Leo Varadkar, our current Minister for Health, said that health care had to focus away from hospitals and towards general practice. He would ring-fence cash every year to support the development of GP services and primary care. He spoke about the need for GP’s to lead in community care. He hoped that the large cuts experienced by general practice would be reversed from 2017, and that some allowances could be restored before then. He also indicated that expanded roles for pharmacists, community nurse, and others were on the way.

The Sinn Fein speaker, whose name I missed (apologies), urged free access to primary care, an increase in training places for general practice, and the introduction of some salaried GP posts.

Deputy Róisín Shortall spoke for the Social Democrats. She acknowledged that integrated care was vital, and that they aim for a single tier health system with much greater capacity in primary care and more innovation in care. She also felt that there would be little more money for health.

The FF spokesman, Senator Thomas Byrne had two good ideas, first that health care planning needed to run over many years; second, that the primary care budget should rise by €160m a year each year; and one very bad idea, that while they were happy to see free GP care extended, this should be on the basis of need, and not based on such factors as age. I advise them to read the Keane report, from September 2014 carefully, where the impossibility of this is carefully explained.

The FG spokesman, Senator Colm Burke, said that they would need to resource GP care properly, but felt that change would be hard, and that the health budget would not increase much over the next while. He also talked about primary care.

Conclusion

The solutions proposed by the GP’s and the IMO are straightforward enough. They can be delivered, and will, almost certainly, save money.

One big threat is the lack of capacity for change within HSE and the Department of Health. Although working models of community diabetes care have been evaluated in Ireland, and running for over 20 years, there is still no serious plan to implement and resource this most basic level of care, for one of the commonest chronic diseases, across the whole country. (There is a plan, but not a credible plan.) At the current rate of progress, chronic disease care in Ireland might be up to scratch in forty or fifty years. This is not acceptable.

The other threat is the lack of money. Overall, the Irish health care spend is quite reasonable. We spend a little below the OECD average per head, based on our GDP. Based on our GNP, which is a better measure for Ireland, we spend quite a bit above the OECD average. There are problems with these figures, but the overall conclusion stands. The problem is that we seem to get poor value for money, both from the public sector, and, especially, from the private hospital sector. To change how we deliver care, to move to a more efficient service, we will need to invest more, and quickly, in general practice. This will need an increased health care budget, rising by 6% to 8% a year.

If both of these cannot be delivered, then the most likely outcome is that the health service will continue to get worse, queues will continue to get longer, and preventable ill-health from chronic disease will continue to rise.