If you know me, you will know that I am not the most dexterous person. I was never going to have a career as a surgeon. I read a paper some years ago that gave me hope that I might yet improve (not that I might take up surgery). I vaguely recollected that the authors had shown evidence of unexpected brain plasticity in older people, by documenting structural changes in the brain after teaching people how to juggle.

I was talking to a colleague from our Business School the other day, who, it turns out, is interested in brain plasticity, and functional MRI studies as part of her work in the Business School in DCU. I mentioned this memory to her, and she was very interested, so I went off to find the paper.

I did a little digging in PubMed, and eventually found two papers dealing with the impact of learning to juggle in older people.

The first looked at the effect of age on the ability of people to learn to juggle.

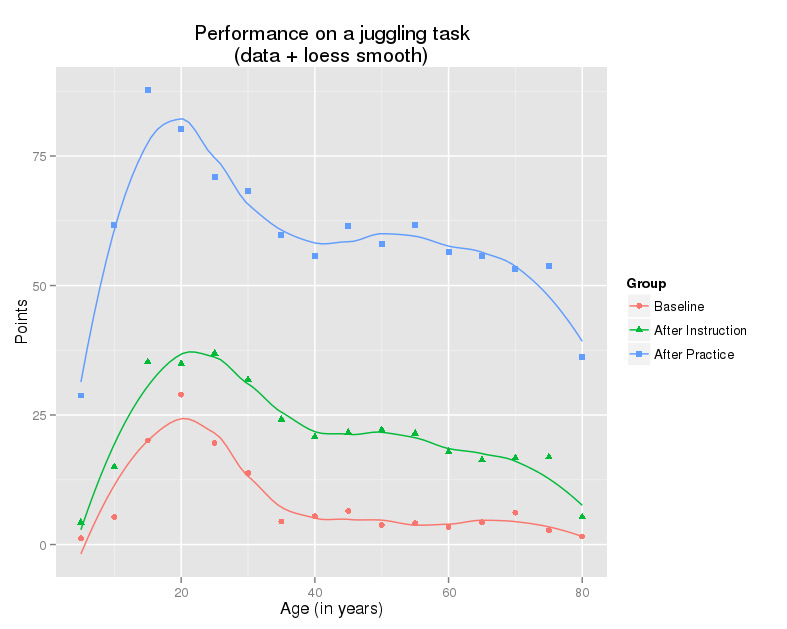

Performance on a juggling task by age, at baseline, after instruction and after practise. (Source – redrawn from Voelcker-Rehage C, Willimczik K, Motor plasticity in a juggling task in older adults-a developmental study. Age Ageing. 2006 Jul;35(4):422-7.PubMed PMID: 16690635.)

This graph shows the main results. There were over 900 people, across a wide range of ages (6 to 89). Each person was scored on video, doing a juggling task, first without instruction – ‘Baseline’, then after verbal instruction ‘After Instruction’, and then after 7 sessions of practise -‘After Practise’. The key finding was that, while people aged 15 to 29 did better than anyone else on this learning task, there was little indication of any further decline in performance with age.

The second paper compared MRI scans over 6 months of 69 older people (mean age 60) who were taught how to juggle. The first scan was a baseline, the second after three months, with (more or less) regular practise, and the third after a further three months, with no structured practise offered. They found that a particular area of the brain, known as the human middle temporal/V5 complex, which apparently plays a central role in the perception of visual motion, increased in size by 3 months into the study, and shrank back again by six months. There other changes in brain structure as well. These were similar to the changes they had found in a group of 20 year olds, in an earlier paper.

What does all this mean? From my perspective the most interesting finding of neuro-scientists over the last 20 years is that the human brain changes over time. Work on brain development in late adolescence and early adult life, has shown that ‘adult’ brain structure is not reached until the mid twenties. This capacity for development continues throughout life. This ties in with the evidence that learning can slow the development of Alzheimer’s disease – literally use it or lose it..

The work on juggling shows that we retain, into old age, the capacity to learn, and that this capacity does not decline much, if at all, with age. We have the capacity to change our brains as well as our minds.

Technical details – the graph is drawn in R with ggplot2. The data were digitised using xyscan.