I was asked to speak earlier this year at a seminar on ‘Co-op Care – Co-operatives and elder care in Ireland’, organised by the Society for Co-operative Studies in Ireland. I’ve now had the opportunity to put these materials up, together with the original presentation.

There has been lot of concern about the impact on Ireland of our ageing population. Some concern is warranted – there will be more older people in Ireland than there are now, both in absolute numbers, and as a proportion of the whole population. This fact needs to be accommodated in planning and budgeting for both the short, and the long, term.

There is good evidence that this shift in demography can be easily accommodated in Ireland – primarily because our EU peers are well ahead of us in having ageing populations, and they seem to be doing just fine. This didn’t happen by accident, but by detailed, careful, planning and working with older people to ensure that their needs were met, and their choices accommodated.

Demographics

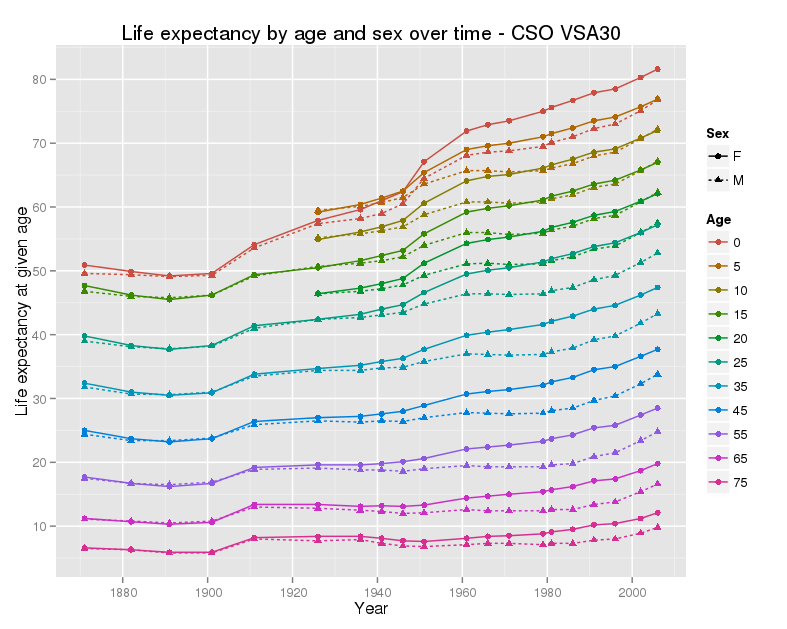

The number of older people in Ireland is rising, and rising fairly fast. This is for a really good reason – life expectancy is rising steadily, and continues to rise.

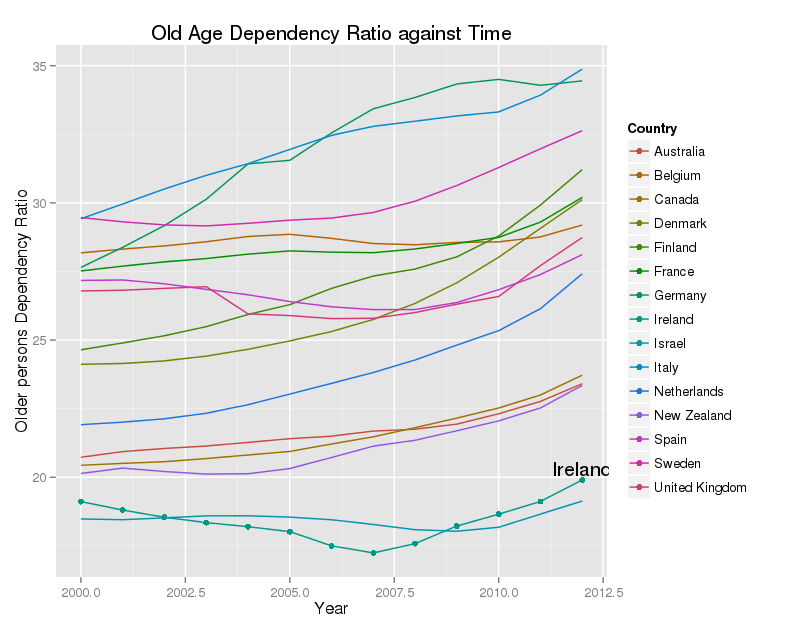

The implication is that the proportion of older people will rise too. However this also depends on the number of births. Ireland has and maintains a relatively high birthrate. There is a measure – the ‘Old Age Dependency Ratio’, which reflects the number of older people per working age person in the economy. To be exact, it is the number of people aged 65 and over, divided by the number of people aged 15 to 64 (and multiplied by a hundred). The next graph shows this for a set of OECD member states.

Ireland has one of the lowest OADR in the whole EU, and while it is rising, it is nowhere near that in most of our peers. The number of older people is rising, but there are many more younger people, partly as a result of immigration, and partly as a result of historically high fertility rates. The OADR will rise, and will rise quite quickly in Ireland. The CSO predict that it will be about 30 by 2031, and about 40 by 2046. This will be a real challenge to us, but nothing that most of the rest of the EU has not already faced.

Health, and death

It’s a commonplace phrase that 70 is the new 50, but it conceals a real truth. Although people are living longer, they are also staying healthy for longer. In the 1920’s a man of sixty-five was old, and was likely to be frail. This is no longer true. The inelegant phrase used to describe this is ‘compression of morbidity’. Most people are reasonably well until the last year or two of their lives, and this has not changed, although the last year may occur now in their eighties, and not their sixties.

The main users of health care and social care are older people shortly before they die, and a group of people, across a wide span of ages, who are affected by more than one long-term illness – which is referred to as ‘multimorbidity’. The implication is that this is the group for whom our health services needs to work best. There is reasonable evidence that a combination of well-organised primary care, active intervention to maintain health, mobility, and maximal independence, and support for self-care, can improve the quality of life for this group of people, and reduce health care costs.

Responses

There are two responses to the issues described here. The first is to seek to induce panic – essentially arguing that this cannot be afforded, and that social and health care need to sharply pruned if the economy is to survive. This is not true – a detailed analysis is given by Bloom et al, in the Lancet paper listed below.

The more constructive response is to decide to cope with the issue. This is eminently feasible, and many other wealthy economies have already done this. The idea is simple enough, although the implementation is not! There are three objectives:-

- Prevent morbidity

- Defer disability

- Support independence

These can all be achieved by restructuring, funding and incentivizing our health and social care systems to do so. There is good evidence for many effective actions to reduce long term ill health, starting before conception, and running up to the age of 80 or more. There are interventions for all ages, men and women, including lifestyle changes, environmental changes, health care, social support, community development and more. These are all feasible, but many fall outside the current scope of our health services – however, this can be changed.

For older people, services need to be made more client centred. Services must identify and meet the needs, of their clients, not the needs of the delivery organizations. Indeed this would be good advice for most health and social services! Most older people want to live in their own homes, or at least in the same area. This means that support to help older people needs to be community based. I would argue that their aim ought to be to help people to live as independently as possible, in the location of their choice. Certainly we ought not to drive people into long-term care settings.

All of this is feasible, and affordable, but as I said earlier, it will not happen by accident – as the saying goes ‘Plan, or plan to fail’. Our older people deserve better.

Selected resources

There are a series of Lancet papers, published in February 2015, on ageing and health – all are worth reading.

- Suzman R, Beard JR, Boerma T, Chatterji S. Health in an ageing world–what do we know? Lancet. 2015 Feb 7;385(9967):484–6.

- Mathers CD, Stevens GA, Boerma T, White RA, Tobias MI. Causes of international increases in older age life expectancy. The Lancet. 2015 Feb 13;385(9967):540–8.

- Prince MJ, Wu F, Guo Y, Gutierrez Robledo LM, O’Donnell M, Sullivan R, et al. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. The Lancet. 2015 Feb 13;385(9967):549–62.

- Chatterji S, Byles J, Cutler D, Seeman T, Verdes E. Health, functioning, and disability in older adults—present status and future implications. The Lancet. 2015 Feb 13;385(9967):563–75.

- Banerjee S. Multimorbidity—older adults need health care that can count past one. The Lancet. 2015 Feb 20;385(9968):587–9.

- Steptoe A, Deaton A, Stone AA. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. The Lancet. 2015 Feb 20;385(9968):640–8.

- Bloom DE, Chatterji S, Kowal P, Lloyd-Sherlock P, McKee M, Rechel B, et al. Macroeconomic implications of population ageing and selected policy responses. The Lancet. 2015 Feb 20;385(9968):649–57.

Three papers on compression of morbidity :-

- Forma L, Rissanen P, Aaltonen M, Raitanen J, Jylhä M. Age and closeness of death as determinants of health and social care utilization: a case-control study. The European Journal of Public Health. 2009 Jun 1;19(3):313–8.

- Payne G, Laporte A, Deber R, Coyte PC. Counting Backward to Health Care’s Future: Using Time-to-Death Modeling to Identify Changes in End-of-Life Morbidity and the Impact of Aging on Health Care Expenditures. Milbank Q. 2007 Jun;85(2):213–57.

- Fries JF, Bruce B, Chakravarty E, Fries JF, Bruce B, Chakravarty E. Compression of Morbidity 1980-2011: A Focused Review of Paradigms and Progress. Journal of Aging Research. 2011 Aug 23;2011, 2011:e261702.