There’s been a lot of discussion about public sector salaries over the last few days, and in particular about consultant salaries. A revised salary scale has been proposed for all newly appointed consultants, raising the starting and final salaries significantly. At the same time there are pre-budget murmurings about raising public sector salaries again. I am, of course, a public sector worker, so I am not entirely disinterested in this. My 2c are that if any public sector salaries are to rise, this rise should be confined to the lowest paid workers. People like me, on high salaries, ought not to be getting a sniff of a salary rise for several years to come.

Leaving that to one side, I want to look at the evidence on consultant salaries. I am a doctor, but I’m not a consultant. I’ve worked in hospitals for quite a few years, although not recently, and I spent a lot of time as a patient a few years back. I also work with quite a few consultants, and trainees (i.e. non-consultant hospital doctors) on various research projects.

The question being asked is simple enough. Are Irish consultants well paid, or poorly paid, by comparison with their peers? The context is two-fold; first, there is a really serious problem getting people to apply for and accept consultant posts in Irish hospitals; second, consultant salaries were cut quite sharply, like most other public sector salaries, between 2009 and 2013.

What is the evidence? The main source is the OECD Statistics database. The OECD collects a lot of information about various aspects of the health services in their member states, and they put a lot of effort into making these as comparable as possible. They collect information on the incomes of medical consultants (Health -> Health Care Resources -> Remuneration of health professionals). For Ireland, the OECD only collects information on the salary of consultants, not on their private earnings. These earnings are quite substantial, a point to which I will return. The OECD presents this information in a number of ways, each of which tells a slightly different story.

First a caveat, while the OECD does a lot of work to make these figures as reliable as possible, there are still big problems. All the data are averages, so you can’t compare pay-scales directly. The pension levy is not deducted from the Irish salaries, but it is definitely deducted from the take-home pay. The salaries exclude private practise income, which varies hugely. No data is collected on the up to 500 (or so) fully self-employed private consultants in Ireland. UK data may not properly account for merit awards. What is classified as a consultant in one place, is not necessarily a consultant elsewhere. In a word, these data are usable, but not necessarily always right.

I’ve done a series of graphs, each of which I will discuss separately. In each of these graphs each country has a different colour. Those self-employed( dots) and those on salaries (solid line) are drawn with different types of line. Ireland is always shown as a solid line with large dots added, and this line is labelled as well.

Specialist incomes as a proportion of the average wage

This graph shows, for a wide range of OECD countries, the incomes for salaried and self-employed consultants, as a proportion of the average wage, from 2000 to 2012. For Ireland in 2012, this figure was 3.65, so in that year an average Irish consultant earned, from their salary alone, more than 3 and a half times as much as an average Irish worker. Irish consultants are towards the top of the salary scale. Their actual salary fell sharply, but so did everyone else’s, so the proportion is pretty flat. The other thing to notice is that self-employed consultants make far more money than salaried consultants. There are issues with accounting fully and properly for their costs in running the practise, but the overall message is pretty clear. Note that there are no data on private income for Ireland.

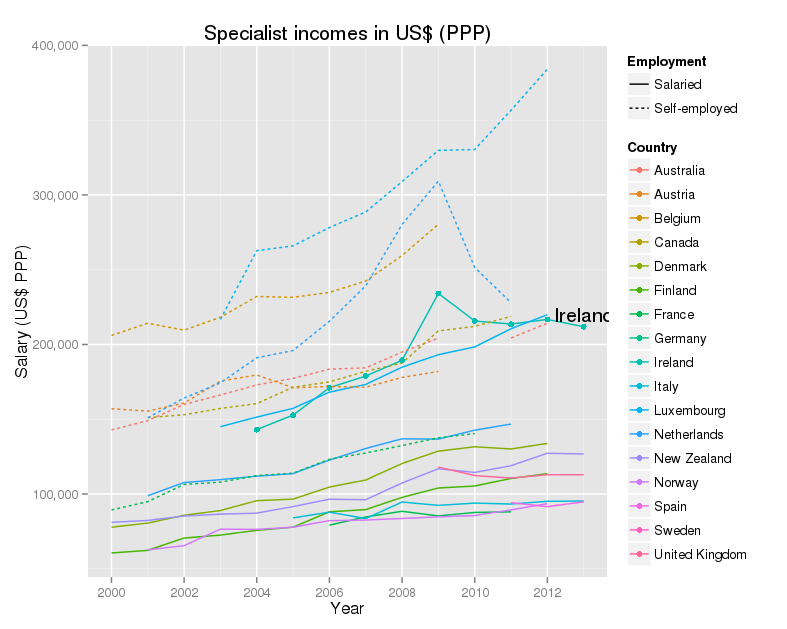

Specialist incomes in US$ at purchasing power parity

A different way of looking at the same figures is given by using a common currency. In this case the OECD use what are called “US dollars at purchasing power parity”. The idea is that money, even in a common currency, is worth less where the cost of living is high. OECD calculates a rough equivalent, between countries, and over time, for the amount of money that will buy an equivalent lifestyle, allowing for these varying costs. The story this graph tells is very similar. Irish consultants do well, coming at the top of the salaries with their colleagues in Luxembourg. Self-employed consultants do better.

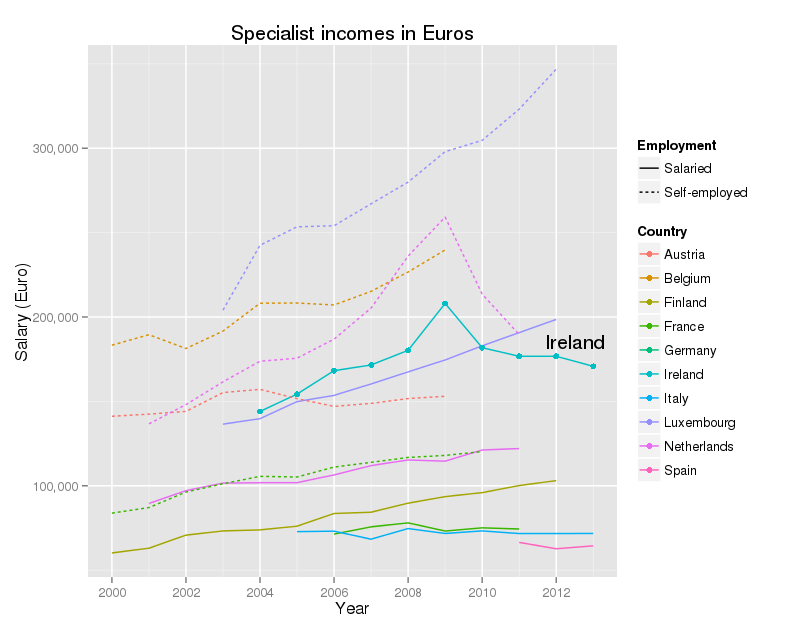

Specialist incomes in Euro

US dollars at purchasing power parity are all very well, but not exactly familiar. Euros are probably more useful for most of us. This graph shows the data for the Eurozone countries only. The picture is very similar to the previous graph.

What does all this tell us?

Allowing for the limitations of the data, I do not think that one can argue that Irish consultants are underpaid. I do think that they deserve high salaries – being a consultant is a tough job, with long hours and heavy responsibilities. Part of the confusion is that the salaries of Irish consultants are being compared with the incomes of self-employed consultants in other countries. Their salaries are notably lower than the incomes of self-employed consultants in other countries, but this is what you would expect.

What isn’t known, as far as I know, is the total income of Irish consultants. It is known that the private insurance companies pay about €360 million annually to the consultants, but, again as far as I know, there is no information on their office fee income, nor on the other costs that have to be met from this income (e.g. rent, office staff and so on), nor on how these fees are distributed (there is enormous variation in the private practise incomes of Irish consultants). It would be useful to have these figures.

The figures we do have suggest a need to ask a very serious question. Given that the salary covers only a proportion of the income of our consultants, how much should they receive, in total, as a fair compensation for their difficult and challenging work? I don’t have an answer for this, but I think that there is a real need for a careful, objective discussion of the topic. Consultant salaries are a sizable proportion of our total health expenditure, and we have to make sure that we are getting value from this spend.

My other question was “why is it so hard to recruit people for consultant posts in Irish hospitals?” As far as I know, no-one really knows, although there is a study going on at the moment. Pending the results of this work, there may be some clues in the latest Medical Council report on the medical workforce. Striking features are high rates of withdrawal from the register for younger doctors, and a very high proportion of doctors (1 in 3) who qualified outside Ireland. None of this suggests a service that is very attractive to its own.

Talking to colleagues over the last few years, the impression I have is that many people are unhappy about coming to work in Ireland. Some points people have made to me :-

- Almost all consultants work very hard, and work very long hours

- Most work significantly more than their contracted hours in the public sector

- Our health system is complicated, with poor communications, mostly by mail, fax and telephone

- Hospital bed utilization is extraordinarily high by international standards

- Primary care is critically underfunded, so a great deal of that work lands back into the hospitals

- Information systems are weak, and many processes are done manually, that have been automated in other countries for many years

Nonetheless salary cuts matter – I was enlightened by a colleague who drew my attention to the final report of the Strategic review of medical training and career structure. One of their recommendations (page 81) is :-

“The Working Group recommends that the relevant parties commence, as a matter of urgency, a focused, timetabled IR engagement of short duration to address the barrier caused by the variation in rates of remuneration between new entrant Consultants and their established peers that have emerged since 2012.”

I gather this was based on strong representations from trainees who met with the group, who intimated that the salary differential (of 30% between new entrants and existing staff) was the main factor, though by no means the only factor in their decision making.

So salary cuts do matter. It is possible that the new salary scales will produce the desired flood of people applying for posts in our services. I certainly hope so. However, I remain of the view that we need to fix many other issues in our services as well, if we are to keep these people working here, and have a decent and affordable service.

Acknowledgments

Colleagues, who had better remain anonymous, unless they wish to comment below, have very helpfully critiqued my observations. I appreciate this. I have a better grasp of the limits of the OECD data, and have found work on the attitudes of senior trainees to the lowered salaries for new entrants – their views were very negative. I was wrong to argue that salary cuts were relatively unimportant – they were (and are) important, but still not the whole story.

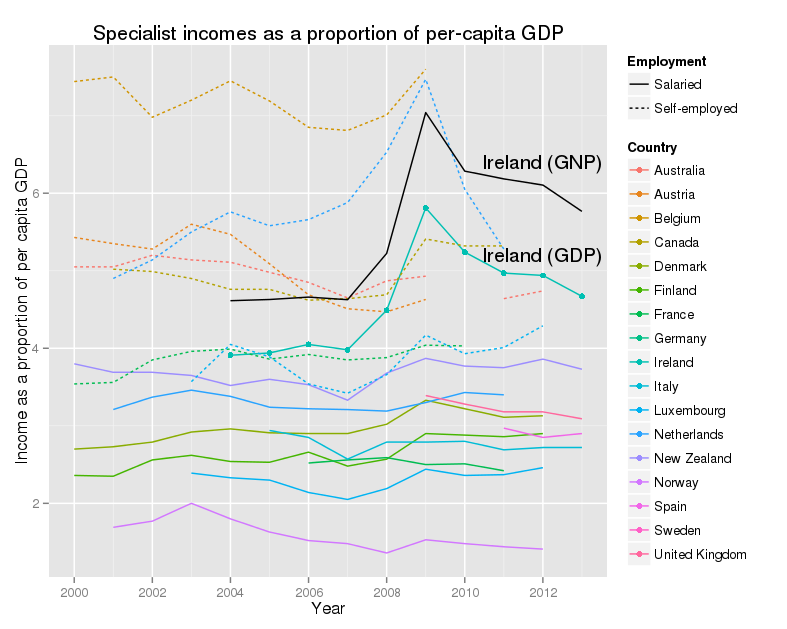

Appendix – specialist incomes and GDP/GNP

The OECD presents the earning figures in one further way, by comparison with GDP per capita. This is a very rough guide to the wealth of a country. Because Ireland is the home to a large number of multi-national companies, with very large exports, Irish GDP is not regarded as the best guide to the size of the economy. GNP is preferred. The CSO publish GDP:GNP ratios annually, and the latest published is for 2012. The ratio has fallen from about 0.85 in 2004 to 0.81 in 2012. I’ve assumed that the figure for 2013 will be similar. I’ve calculated the salaries of consultants as a share of the per-capita GNP, and added this to the graph.

This shows a similar story to the other graphs, with one interesting twist. What is very noticeable is that Ireland is now much further up the rankings, both for GDP, and especially for GNP. This says, that relative to the wealth of the country, our consultants are well-paid. Again this excludes their private incomes. The peak in 2009 reflects the collapse in GNP, and not a rise in consultant salaries.

Technical note

The graphs are done in R using Hadley Wickham’s elegant ggplot2.

My colleague, Alan Irvine from Trinity, added the following, which I think give further valuable perspective on the matter. I agree with much but not all of his comments.

I agree it is hard to attract consultants to posts in Ireland, this is a simple fact that we see on the frontline and it is having a def, inite impact on the ability to provide patient care. It is also absolutely true that money is not the only or even the primary determining factor. Here are a few thoughts that I hope will inform your thinking on the issue.

The experience of practicing hospital medicine in Ireland

The simple fact is that over the last 6 years, since the 2008 consultant contract, the HSE has become an increasingly unpleasant and unrewarding place for consultants to work. Every new reform has centralized power, making decision makers remote from front line services. We have severe structural problems that have significant impact on a consultant’s professional life (underdeveloped Primary care, lowest number of specialists in the OECD, lowest ratio of specialists to generalists, highest ratio of administrators to consultants (7:1, UK is next closest at 3:1), way too many acute hospitals (35) with already low numbers of experts spread too thinly to safely practice at 2014 levels. If things go wrong in these under resourced environments, consultants are the fall guys. When we come to have our practice reviewed, it is by the only lay majority medical council in the OECD. Patient expectations have risen (rightly) at the precise time the service has been stripped bare. To summarize, the public administration and infrastructure of our health service is, on its very best day, barely adequate, and on an average or poor day, toxic, unpleasant and dangerous. Newly appointed consultants routinely start their appointment with no admin support, no junior doctor support, no outpatient or theatre slots, no office. It is taken as standard that they will spend the first 2-3 years fighting for each of these resources to craft a service that is safe and adequate.

I’ll highlight a few areas that might further inform your analysis.

Management side approach to consultants

There has been a clear anti-doctor agenda in recent years, with its roots in a 1970s vision of what consultants were, how they behaved and the need to ‘cut them down to size’. This outdated, doctrinaire approach informs public discourse (including with respect and to a degree, yours, of which more below) and public policy. Unless and until we adopt an evidence-based approach and a culture of respect from management for what consultants actually deliver, the situation is likely to deteriorate further. Even now with the current proposals, the IHCA is excluded from negotiations on a technicality and the HSE head of HR is advertising posts with conditions that haven’t been agreed with the IMO. It is hard to see that management is actually trying to deal constructively with the issue. Remember the 2008 contract had a gagging clause that was eventually removed but reappeared in the draft GP contract. Management value control over outcomes, safety quality or evidence based decision management.

There has been so much repeated bad faith on the employer side since 2008 that trust is now non-existent. “Good will” is hard to monetize and will only be truly appreciated when it is lost. Under the last minister of health, good will was shredded. Salaries were cut sharply, but for new entrants an additional 30% was applied above and beyond every other public sector worker. Consultants got special treatment. Minister Reilly went on the record to say cuts like this would give him a ‘warm feeling’. Consultants and doctors in training remember this and question why they should stay in such a system.

So, money is not everything but as it is the central piece of your analysis I’ll respond to that too. I agree the OECD figures are unreliable; they are not fit for use in such an analysis. As you know, if the raw data are dodgy the analysis is pointless.

Competitor countries

The first point I would make is that our competitor countries are Anglophone ones (Australia, USA, Canada, Australia, Middle East). If your analysis is designed to inform the debate as to why 30% of our doctors are non-Irish trained and why 10% of 25-29 year old doctors are leaving year-on-year, salaries in Luxemburg are irrelevant. There is no significant transfer of doctors between continental Europe and Ireland or vice versa, EU specialists are many more in number and less well trained. University hospital academics are a more relevant comparator group in the EU. In the USA these comparisons break down entirely. For example in a single hospital a plastic surgeon or cardiologist may well earn x5 that of a geneticist. The variance between hospitals and states is even greater. A mean earning figure really means nothing in such a dataset.

Private Practice

Several times your analysis mentions private practice but only in an Irish context. This reflects outdated thinking as mentioned above. The fact is that since 2008 new consultants have been barred from off site private practice. A ‘C’ contract category was agreed in 2008 but for many years (more bad faith) the HSE refused to agree to appoint the agreed number of C contracts. That was poor for recruitment but also for service provision. In the UK there are no limits on consultants Private Practice. VHI don’t release individual consultant payment levels but they do say that 80% of consultants get less than €100K. So certainly some earn very well but most are in whole time PP in Beacon, Bons, Mater private, Blackrock etc.

‘Purchasing power’

I must confess I don’t understand your calculations on purchasing power. Simply put, this means how much a worker can buy with her/his net (post tax) earnings With the new salaries in 2012 we have tried recruit to the public service on salaries of €99-116K. Let’s take €110k as a working figure. 55% of this is removed at source, leaving a net salary of €49, 500. Deduct from that medical insurance (100% increase in last year), CPD, membership of societies, journal subscriptions (again needlessly recently changed by the HSE), and medical council membership (the non-tax deductible costs of being a doctor) and you are left with maybe 42K per annum, or net monthly €3, 500. A small extra allowance is given the consultant works every third weekend or more (a 1:3 rota).

The average profile of a new consultant is a woman or man of around 34-35 who has general excelled at school and who has spent approximately 16 years between undergraduate and post grad training. Usually they have no ownership of accommodation due to the peripatetic nature of their training and they often have run up substantial personal debts paying for training overseas. Often they have childcare needs. Dublin is the second most expensive city in these islands. I’m afraid in Dublin €3, 500/ month compares poorly with starting salaries in UK and certainly not elsewhere. Several of my new consultant colleagues are back living with their parents. Remember we are askin>g these senior professionals to undertake very significant responsibilities, with 24/7 cover and availability.

Real life examples

Given the lack of reliability of the OECD data, real life examples may be more helpful to help you understand why recruitment is slow.

I have, in the last year, taken calls from 2 really excellent trainees doing fellowships in Canada. They would be fantastic additions to the Irish health service. In each case they have been offered packages to stay on in their training hospital as consultants. The working conditions are excellent and they have been offered Canadian 450K as a starting package, with a 4-day week. How can I attempt to bring them back to Ireland?

A second example. One of many. This year 19 trainees completed training in anaesthesia, an area where the HSE has a real need. None of these 19 intends to work in the Irish public service. They will work in the independent sector or overseas.

Conclusion

I agree with your conclusion that money is neither the entire problem nor the entire solution but we need to be fact-based in how we report the actual monetary rewards on offer and how they actually compare with the independent sector in Ireland and in other competitor systems overseas. Taking a broader, picture management needs to reimagine its approach to consultants. They can and have used their power to make consultant’s lives miserable but we don’t live in Cuba and they can’t make consultants stay around to take more of it. The HSE are not the only employment option available. An urgent rethinking is needed. Simply put, if Ireland doesn’t value the doctors it produces, other countries do and they are open for recruitment. I should add this problem is not exclusive to consultants or doctors, the same HSE is struggling to understand why new nursing graduates won’t work here for €9/hour.

I fear the situation is certain to become worse, rather than better and I agree with your analysis that the current approach is unlikely to solve the issue.