One of the regular features of the Irish healthcare system is a series of ‘Trolley numbers’ – this refers to numbers of patients who have been assessed as requiring admission, but who are waiting for a hospital bed. Some wait on chairs, some on trolleys scattered around our Emergency Departments (ED’s) and some in extra beds or trolleys on hospital wards.

This matters for a number of reasons.

First, there are significant patient safety, and dignity, issues – it is impossible to provide adequate monitoring for an ill patients sitting in an ED corridor, perhaps tucked in behind another patient, perhaps in a side room. It is also very hard to provide patients in this situation with privacy, not to mention food, access to toilet facilities and washing. Speaking from personal experience of spending time on a trolley in a busy ED, it is very hard to rest, impossible to sleep, and generally a miserably uncomfortable way to pass a day, or two, or three.

Second it causes blocks further back the chain. At worst patients may be left sitting in ambulances in the ED car park. This removes an ambulance and crew from service, which is itself dangerous, and puts the lives of others at risk too.

Finally it makes it very hard to work in ED, especially for nurses, and the patient care staff, such as catering staff, nurses aides, and porters. All do their best, often going well beyond their usual jobs to help patients, but it is far harder than it ought to be.

This is, of course, a scandal. It would not be unreasonable for a few patients to be on trolleys, for a day or so, if there were some major incident, but this is now a regular feature of Irish hospital life. In most hospitals in Ireland, there are always a few patients on trolleys, and there are often twenty or thirty patients. This is not on, but it is now part of the normal operation of the Irish hospital system.

As can be imagined, this attracts huge public attention. We have just had a new record, of 612 patients on trolleys, and the media have focussed on the topic. The Minister, Simon Harris, a Fine Gael TD from Wicklow, has been quizzed about this, and about his response. To summarize, he blames a serious influenza outbreak, and a lack of preparedness in hospitals, despite an extra €40m in extra winter funds given this winter.

There is some truth in both explanations, although I notice that there were 600 patients on trolleys this time last year, with a very mild flu season. I am also aware of the huge effort that the acute hospitals have put into reducing trolley numbers. Irish hospitals have a broad range of in-hospital responses, including medical admission units, seven day discharge ward rounds, senior medical staff in ED, active bed management, and community liaison. They could do more, but honestly it isn’t working, and if I’m right, it won’t work.

I think that what we are trying to do, is a bit like treating a patient who presents with a pain in their left elbow for a sprain, when their real problem is a heart attack. Unless we can assess the cause of the trolley waits, we are not going to be able to fix them.

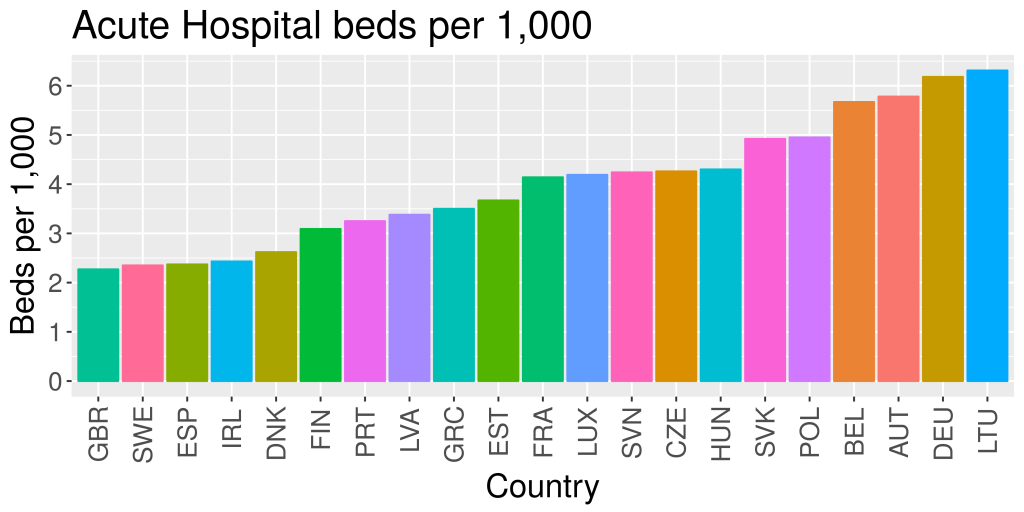

The main public response from my colleagues both in hospitals, and in general practice goes like this. OECD data show that Ireland has 2.4 acute hospital beds per 1,000 population, amongst the lowest in the OECD. The average is about 4.3. If we could increase our hospital beds to the OECD average, all would be well. I respectfully disagree.

A more considered analysis goes like this.

OECD countries have very different health care systems, and very different histories. Ireland is one of a group of countries, including the UK, Spain and Sweden with relatively few acute hospital beds. Belgium, Germany, Austria and Lithuania top the EU table with three times as many beds as we have. This, in itself, is not a good measure of health system performance. Ireland has got one of the most expensive health care systems in the EU, but it would be hard to argue that it is one of the best. What really distinguishes us from our peers is the very low investment in primary care.

I believe that we do not use our hospital beds effectively. We certainly use them a lot, with bed occupancy rates well over 95% for most hospitals, which is far too high. There are plans, for at least the last 10 years, to do a bed capacity review, and Minister Harris now tells us that this will be done by the first quarter of 2017. This ought to provide a clearer answer to the question – how many beds do we need, and how should they be divided, between, say , ICU beds, HDU beds, emergency beds, elective beds, and so on.

As it is at any given time we have the equivalent of one of our large teaching hospitals, in beds, full of patients awaiting discharge to community support, but that support is not there. We have grossly excessive waiting times for appointments, and for outpatient investigations. Capacity for doing such work outside acute hospitals is almost non-existent, unless the patient has health insurance.

In other countries there is a more strategic approach. This starts with an analysis of costs. Most health care spending is used by a small number of patients. These are, largely, patients with multiple illnesses, and often, other non-health problems. There is now good data, form several countries, showing that active case management and integrated care for this group of patients reduces costs, and improves the quality of their lives. To do this, resources are provided in the community to do the case management, and to work with the patients to keep them healthy.

This requires integrated care between hospital and primary care, and between health and social care services. Ireland, unlike many other countries, has health and social care provided by the same organizations, but we derive no benefit from this, because we do not provide for integration between them. There is, of course, good practice on the ground, but this has never been scaled up and rolled out across the system.

A key element if we are to do this is to properly fund primary care. Irish GP’s have their own crisis coming down the line, with an ageing workforce, limited investment in services, premises, and staff, and a 40 year old contract which was out of date when it started, and now represents a major obstacle to progress. The Department is finally negotiating a new contract, and there is some hope that whatever emerges will be fit for purpose. There isn’t a lot of time to get it right though.

What might a new system look like? My own idea is a service centred on patients and their needs, in which, for most people, most care will, as at present, be delivered in the community, at home, or in their local practice. Practices will be better staffed, and offer a wider range of services to their patients. To make all this work we need integrated care – this is sharing of care, information, and resources between the patient, and all those involved in their care, GP, hospital clinic, social care, and others.

For most patients this poses few challenges. However, there is an important subgroup of patient, a group of people with more complex health care needs, and often more complex social care needs, who need more. For this group, who are less than 5% of the population, but who are responsible for more than half of all health care expenditures, there is now good evidence from studies in many countries, that effective integrated care can cut costs, reduce hospital admissions, and improve their quality of life.

To make this possible, we will need skills and investment. We will need to draw on good ideas from within Irish health care, and further afield, but given that, we can train people and develop the skills to make this happen. To pay for this we will need to shift resources from acute hospital care to community care and general practice. This will require significant extra investment to cover the costs on both sides as we make these changes. In 2017 Primary care is due to get an extra €30 million from the HSE service plan. This isn’t nearly enough. It’s hard to estimate what is needed, but a rough figure would be about €600 million a year extra in primary care. This would be reached over a few years, and would be counterbalanced, to an extent, by smaller increases in hospital care costs, as services and staff were transferred across.

More fundamentally we need a direction of travel. One of the reasons why the Irish services are so expensive and work so poorly is that there is no agreed vision for the future of Irish health care. Most of those involved are fighting their own corners. This is quite understandable, but it’s not getting us anywhere. There is an Oireachtas committee on the future of healthcare, whose report has been postponed until April. If the Irish state, and the Irish health services can get behind a credible vision for the future, and work towards it over 5 to 10 years, then there is some hope that we could end up with a sustainable health service. If we don’t know where we are going, we’ll get nowhere. This is the real challenge for Minister Harris, and for Ireland.